Last week, I published Debunking the Fertility Crisis, which proposed what I call “reproductive anxiety” as the basis of moral panics like the “fertility crisis” and the “sperm count crisis”—neither of which are based in sound data or workable hypotheses, but shoddy statistical witchery and commercialist trickery. It’s not what’s said in these hypotheses that’s a problem—it’s what isn’t said. Omitting chunks of context paints a bleaker picture in such a way that one can’t help but think it’s intentional, teleologically pointing towards political ends that both sell well and fuel an army of unhinged online rabble-rousers. If you missed that piece, here it is:

Debunking the Fertility Crisis

My friend Pete was from Norway. We met in Los Angeles working at a bar in Universal City, wedged between Hollywood and North Hollywood. Technically Norwegian, by nationality, Pete was born to American parents overseas in the military. He came back to the U.S. and went to college in Oklahoma before…

But this wasn’t the whole story. I removed several sections for brevity’s sake, and a glut of writing and research wound up on the cutting room floor. The stripped-down version of the argument was robust enough to stand on its own. There was a portion on testosterone and more, so an addendum is needed. As usual, I’ve brought visual charts.

Now, for those who missed it, a brief synopsis: alarm bells have been raised about numerous reproductive concerns over the past few decades which either didn’t amount to the disasters hypothesized or were overblown by authors, media, and the Internet.

The “sperm count crisis” came after a 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine et al. reported that men’s sperm counts had declined significantly since the 1970s. One researcher, Shanna Swan, went on to write a book called Count Down that claimed we were on the path to living in an infertile world—real dystopian sci-fi stuff.1

The “fertility collapse” panic has been peddled, often by right-wing personalities and some economists, as a looming future crisis as birth rates decline. This panic has been all over the media.

Both of these theories, as well as a third about the decline in men’s testosterone levels over the last fifty years, are misleadingly magnified in the public discourse, and both overlook crucial facts that defuse the conspiracy theories.

The Sperm Count “Crisis”

The marvelous

showed me another meta-analysis published by Hagai Levine et al. in 2021, a follow-up to the 2017 meta-analysis that measured men’s sperm rates and found a decline. It’s not that they were incorrect in finding that sperm counts are down—it’s that the size of the wane of sperm is so minuscule, it can’t possibly make a difference in anyone’s lives, despite at least one of the authors sounding alarm bells that this lowering of male sperm counts presents “a global existential crisis.”The 2021 meta-analysis Carlyn brought to my attention augmented the original findings with more countries, practically the whole world, showing that sperm counts are down across the globe. Such findings invite the mind to speculate that catastrophe is on the horizon. After all, if men can’t generate enough sperm, how will we make babies?

The meta-analysis found:

“Overall, [sperm count] declined appreciably between 1973 and 2018 (slope in the simple linear model: –0.87 million/ml/year, 95% CI: –0.89 to –0.86; P < 0.001).”

In plain English, this says that between 1973 and 2018, men’s average sperm count declined by 0.87 million per year.

This sounds like a lot, but before you rush out to buy those gas-station dick pills, realize that men produce, on average, 129-224 million sperm daily. That’s about 75.555 billion sperm per year, meaning if men are losing 0.87 million per year, that’s only 0.00115% of approximate annual sperm production. Something isn’t adding up in these numbers somewhere. You’ll notice I emphasized the word average above because this effect can only be seen when you average everyone’s total sperm counts together. It’s not like every single man is losing 0.87 million sperm per year. Doing the math, this isn’t a cause for concern, and it’s hardly a “global existential crisis.” Here’s an analogy:

The average recommended diet is 2,000 calories per day, or 730,000 calories per year. If we mapped the size of the sperm reduction onto calorie intake, it would amount to a reduction of 8.3 fewer calories per year. If your diet plan was to cut 8.3 calories per year, you’d never lose any weight. It’s too small of a reduction. Worse, unlike calories, something we understand with near pinpoint accuracy, we haven’t established a firm limit of sperm count on the lower end that reliably leads to infertility, nor is sperm count a reliable metric for any health condition, unlike what Levine et al. claim.

What they didn’t tell you is that the same study did not find a statistically significant reduction in sperm count among fertile North American men, so the authors reframed the category as “Western” vs. “Other,” meaning Latin America, Africa, etc. to yield a statistically significant result in the “Western” population. “Western” is a meaningless term.2 There are no “Western” genes, people emigrated from one country to the next over the forty-five-year period, and any environmental factors that might influence sperm count would surely be global. And even these doctored numbers presented in the least charitable light were still far within the WHO’s healthy range. That’s not scary.

The problems with the hypothesis don’t end there, and the section removed on testosterone clarifies both why the hypothesis has issues.

The Testosterone “Crisis”

The “sperm count crisis” and the “men’s testosterone crisis” are eerily similar. You’ve probably heard people fearfully talking about lowering testosterone levels. You’ve likely heard chatter about hormone disruptors and forever chemicals disrupting your hormones. These fears reverberate unchecked throughout the manosphere.

On April 9th, 2021, unabashed peddler of disinformation, Justin Mares, tweeted that male T levels had dropped “close to 50% in the last 2 decades, and nobody is talking about it.” This, too, proved both magniloquent and false.

Valerie Pavilonis, writing for USA Today, traced the history of this claim to a right-wing website that occasionally dabbles, as most right-wing websites do, in lifestyle fascism, a segment of the alt-right pipeline. Now, we should scarcely discount ideas based purely on where they come from (Alex Jones an obvious exception), but we should be skeptical when scientific claims are impelled to justify political viewpoints.

The 50% figure was ostensibly obtained by adding the sum percentages of two studies, here and here, to make a much ghastlier fifty (even though you can’t sum averages together, you can only average them further). So the truth is, one of those studies found a 22% decline and the other found a 25% decline.

What these panics share—besides the fact that they deal with the squishy topics of sex, gender, and reproduction—is that they both proved to be overblown fears. Further, they amounted to little more than grandiloquent panic for the same reason—that the things being measured and compiled into averages aren’t static.

The Testosterone Reality

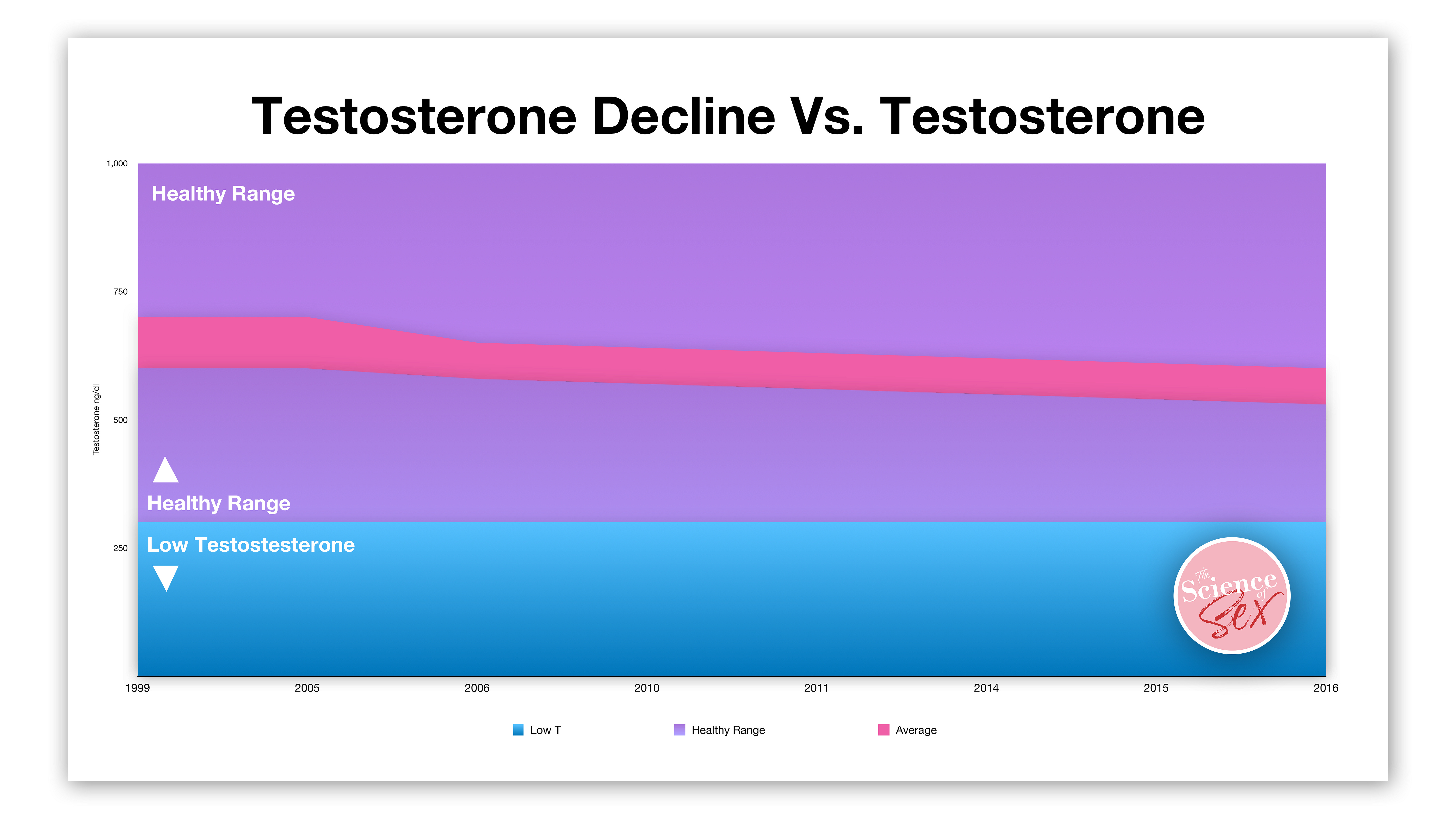

Testosterone is measured in nanograms per deciliter. The “healthy range” of testosterone for men is between 300 ng/dl and 1,000 ng/dl. This means that one man can have 233.33% higher testosterone than another man and both of them are still healthy. But wait, there’s more. This doesn’t count any of the men in the low or high ranges. Men in the low T group can dip below 150 while men in the high T group can exceed 1,500 ng/dl. This is a massive range. The men with the highest T can have testosterone levels exceeding 900% compared to men with the lowest.

A 23% decline in average testosterone levels pales in comparison to the 233% swing between men on the higher end of the healthy range and men on the lower end. It’s a trivial 10% of healthy variation. Not as minuscule as the 0.00115% decline of average sperm decline, but still, it’s well within the healthy range. Another analogy:

If your blood pressure is 110/70, and it rises 2.3 points to 112/73, you wouldn’t be worried. This is still well within the healthy range and isn’t even close to the 130+ of high blood pressure stage 1 or the 140+ of high blood pressure stage 2.

Further, average testosterone isn’t a single number, but a range. The high end of that range is precisely what the low end was twenty years ago. Here’s a chart showing how small of a dip it was compared to the maximum healthy range of testosterone:

And there’s a rather benign hypothesis for why this might be happening. While people have been panicked about all sorts of nasty chemicals getting into our bloodstreams that could be causing this decline, it might be caused by what’s no longer getting into our collective bloodstreams—cigarettes. Nicotine is a potent inhibitor of an enzyme called aromatase. When aromatase is inhibited, it makes the body produce less estrogen. When male bodies produce less estrogen, they produce more testosterone.

This isn’t a weak connection. Aromatase inhibitors are one of the possible treatments for young boys with low testosterone. Now look at what happens when you compare U.S. men’s testosterone levels with rates of cigarette smoking:

Notice these trend lines of average testosterone levels and the percent of the U.S. over 15 years old who smoke. They’re strikingly similar. And the current testosterone range is still hovering near the center of the healthy range.3 This is just one of many running hypotheses that aren’t “the sky is falling, and we’re being poisoned,” and it’s far from scientific law, but it’s got some solid evidence and a workable mechanism. When we pan out and take a wider view, we see the decline in smoking rates spans back decades, to at least the 1960s, and we began taking reliable testosterone numbers in the year 2000:

Finally, both sperm and testosterone measurements suffer from the fact that we aren’t really sure what the “natural” range should be. We only recently started taking reliable measurements, and both testosterone and sperm fluctuate wildly, as mentioned. Both are influenced by physical stress, psychological stress, obesity, insufficient sleep, tobacco, alcohol, and drugs, air pollutants, heavy metals, workplace toxins, and more; all this, and sperm measurement protocols have changed drastically since the 1970s.

Sperm measurements are highly influenced by both collection methods and prior ejaculation. Sperm levels decline markedly if there’s been an ejaculation in the past fourteen days, and it takes approximately sixty-four days to fully rejuvenate.4 I’ve known countless heterosexual men in my life, enough to know that a significant number of guys have no qualms fibbing to gratify their sexual desires. Getting men to comply with the prerequisite that they can’t ejaculate for such long periods of time presents a legitimate challenge for researchers, one that requires trade-offs.5

Fertility Collapse

My piece on fertility collapse covered the fact that, thanks to modern technological progress, the decline in the fertility rate is almost perfectly offset by a similar decline in infant mortality. Fewer babies are dying before their first birthday, and fewer are dying before they reach adulthood. That piece left quite a few things out.

I didn’t factor in the fact that we call them "Baby Boomers" for a reason—because there was a massive jump in the birth rate after WWII, which is precisely when these reliable birth rate figures start. We started taking reliable statistics at the peak of our fertility rate. Imagine if you started taking everyone’s height measurements starting at age 25. It would be easy to mistakenly assume that people don’t get taller throughout life because you weren't measuring the upswing.

With women having fewer babies, we’re going to need to think about how we structure society into the future thanks to the demographic shifts that will occur. Most of us alive now will be dead by the time that happens toward the end of this century. But that’s different from “fertility collapse” which is the conspiracy theory that shifts in the birth rate will lead to such rapid, drastic changes, that society will “collapse.” This would require an extremely rapid transition and zero response to that transition. As I stated in the previous piece, Japan has already hit the point where their population is no longer growing, but they’re the forth-strongest economy in the world thanks to technological development. Sometime between 2080 and 2100, the U.S. will hit the point where Japan was population-wise in 1980, but we’ll have the technology of 2080-2100.

This, too, is pushed for political purposes and most of the people pushing it are really saying they don’t want to think about structuring society in a sensible, or, heaven forbid, egalitarian way, or introducing changes to how we live. What they’re truly saying is they want to stop immigration, which has, historically, been how we here in the U.S. and other countries around the globe have managed population. You can’t have anti-immigrant stances unless you’re going to push native-born women to have more babies because immigrants drive so much of our economy (and economies around the world), so the idea of fertility collapse is inextricable from anti-immigrants stances by sheer necessity.

Take a look at the number of immigrants living in the U.S. from 1960 through 2015:

To someone who’s dead-set against immigration, this looks terrifying. It seems like we’ve opened the borders and just let everyone in. But see what happens when we compare the number of immigrants with the percent of the U.S. that are immigrants:

The percent of the U.S. population that are immigrants has remained roughly steady for nearly two centuries, but the number has grown because our population has expanded markedly. In 1850, the U.S. population was 23 million people; in 2024, it’s 345 million.

So, the sperm count panic and the testosterone scare are more reproductive anxiety, as I called it in my original piece. And so is the idea of “fertility collapse.” Like most conspiracy theories in the modern era, these all have a grain of truth to them, a nugget of research at the center of the lump of hyperbolic coal that’s grown up around them. What worries me, and what makes articles like this necessary, is the fact that, thanks to the age of ad-based media and websites, we’ve grown so accustomed to sensationalist reporting that we reflexively reach for the scariest hypothesis to explain legitimate findings, no matter how small. This is predictably weaponized by political movements.

We must break our reliance on the heuristic that has us reaching for the worst possible explanations for everything health and science related, and that starts with articles like this that call out bad and misleading interpretations of scientific findings.

Pro-tip: whenever someone drops a research paper, especially if it’s one of their first, and then writes a book about it that becomes a bestseller, that’s a red flag. It’s one thing if a researcher has dedicated their lives to research and then writes a book containing their collected findings; it’s another thing when someone publishes controversial research and then immediately starts capitalizing on it. Whether it’s diet, health, sex, sociology, and especially psychology, you have to wonder if they sculpted the research for maximum reach and emotional impact, from which they could later make considerable sums of money.

In science circles, this is called P-hacking, when some unsavory and dishonest researchers conduct a study, they don’t find any meaningful results, so they combine populations or remove some research subjects until they can rig the statistics to look meaningful. It’s a hallmark of dishonest research, and junk science like this needs to be called out.

The 300-1,000 testosterone scale might need revision in the near future because of effects like nicotine, alcohol, and other drugs that had artificially inflated levels last century. This won’t be the first time this has happened. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had to scrap everything we’d learned about anatomy because of our overreliance on the bodies of poor people, which were sold to anatomists, as well as grave-robbing and the use of the corpses of executed criminals, to acquire corpses. By the early-to-mid 20th century, we realized that our idea of the “average” anatomy only represented poor people, as the wealthy and middle class didn’t sell their corpses and could afford secure graves and tombs.

This is a process known as spermatogenesis.

This is likely why it’s been really difficult to set down standards. In an age where everything is measured by metrics, and we explore everything scientifically, it seems so remote and bizarre that there are still many basic bodily functions we can’t easily explore, and this is especially true when it comes to human health because the human body is exceedingly complicated.