Debunking the Fertility Crisis

Should we be concerned about dwindling sperm and fertility collapse?

My friend Pete was from Norway. We met in Los Angeles working at a bar in Universal City, wedged between Hollywood and North Hollywood. Technically Norwegian, by nationality, Pete was born to American parents overseas in the military. He came back to the U.S. and went to college in Oklahoma before moving to Los Angeles, drawn in by the allure of the big-city lights.

One day, the subject of marriage and children came up. Though in his mid-thirties, Pete was both unmarried and childless. He looked at me and said, with a soft-spoken thoughtful seriousness, “I’m glad I don’t have kids, but everyone I know with kids tells me it was the best thing that ever happened to them.”

His concise sentence touched so much at once—the risks, the stakes, the potential for joy (and to miss out on that joy), but also, the possibility that things could go very wrong. It speaks to modern truths both universal and uncomfortable.

Starting a family is among the most important decisions individuals can make, promising immense joy and fulfillment to many individuals, as they embark on the journey of parenthood, experiencing the loving bonds that come with raising a child. It can bestow a profound sense of continuity with nature to nurture the next generation.

But it also spawns unspeakable unease, especially for women, who face unique physical, emotional, and social pressures over motherhood. They’re bombarded with “biological clock” noise about the decreasing fertility rates of aging. This unrelenting pressure coerces urgency and anxiety, fears that are exacerbated by motherhood’s inevitable impact on her career, compounded by a fear of a vanishing independence. Women have every right to be both tepid and timorous amidst the unending onslaught of stress.

Men, too, have parental anxiety, wondering when they’re going to have the chance to build a family and if they’ll pick the right person. These parental pressures smother us, seeds seeping into our cultural discourse that will germinate into panics.

Reproductive Anxiety

One such panic was the sperm-count crisis. Beginning with a 2017 meta-analysis by Hagai Levine et al., alarmist reports rang out that global sperm counts were falling at a dramatic rate, supposedly threatening the future of fertility on a global scale. The researchers reported sperm counts had sunk by 50%-60% from 1973 to 2011.

Shanna H. Swan, one of the researchers from the study, capitalized on her newfound fame, publishing her book Count Down with Simon and Schuster. The book warns that “the modern world is on pace to become an infertile one” thanks to declining sperm rates and Swan further stoked fears, saying, “It’s a global existential crisis.”1

There was just one problem with the sperm-count crisis: it was all wrong. Follow-up research by Marion Boulicault et al. in 2021 found that it was horrendously flawed, but not before the Red Pill movement could embrace it with open arms. Many now believe sperms counts are dwindling dangerously low, irrespective of political affiliation, and the message is pushed heavily online.

Panics like this are born, in my view, out of existential distress about sex and relationships, what I call reproductive anxiety. We worry we’re not good enough, won’t secure a partner, or build a family. As I often remind my readers here on The Science of Sex, picking a romantic partner is an exceptionally new idea. Historically, finding a partner was a sort of res familia—a family affair. Parents picked partners, and you were stuck with whomever you got, which was usually who’d advance your family the most.

Today, we decide our destiny. But, with the freedom to choose comes the anxiety of choosing and the dread of failure. In the words of Jean-Paul Sartre, “We’re condemned to be free.”

Fertility Collapse

“Fertility collapse,” or, “population collapse,” is the idea that global fertility rates are plummeting, threatening humanity's future, often framed as a larger plot to deliberately reduce the population. The conspiracy theory blends concerns about declining birth rates with fears of government control, corporate agendas, or other hidden influences engineering population decline. Let’s call this the deranged version.

Mainstream news outlets push softer variants. The overarching theme connecting them is not enough babies are being born, and soon there won’t be enough young people contributing to the economy, implying “civilization is going to crumble” once we have too many retirees and not enough young people to support them.

The BBC reports “jaw-dropping global crash in children being born,” while CNN chimes in with, “Global fertility rate to plunge in decades ahead, new report says.” Even these are indefensibly sensationalized.

From the BBC:

The world is ill-prepared for the global crash in children being born which is set to have a "jaw-dropping" impact on societies, say researchers. Falling fertility rates mean nearly every country could have shrinking populations by the end of the century. And 23 nations - including Spain and Japan - are expected to see their populations halve by 2100. Countries will also age dramatically, with as many people turning 80 as there are being born.

This soft version is still profoundly misleading. First, because it only selects certain countries where the population is declining the greatest—wealthy, first-world nations—and second because it doesn’t include the whole picture. There are excellent reasons for this decline, which I’ll get to shortly, but first, a bit more about the theory.

Fertility collapse echoes the sperm-count crisis in that both stoke reproductive anxieties. The sperm-count “crisis” promises that, if sperm counts dwindle, people won’t be able to start a family, as male infertility grips the globe. These overlap with the “testosterone levels are plummeting” panic, a topic for another day, and many other reproductive panics. “Fertility collapse” implies that women aren’t having enough babies, and we should pressure them to do so to save humanity’s future.

Elon Musk endorsed the theory, saying “I think one of the biggest risks to civilization is the low birth rate and the rapidly declining birthrate,” when asked how the Tesla Bot would help labor issues. Musk added, "If people don't have more children, civilization is going to crumble. Mark my words."

Fortunately, this too is all wrong, but, like all conspiracy theories, it contains a nugget of truth. Let’s explore why it’s wrong, and debunk some other myths along the way.

Reproductive Reality

Let’s start with the basics. Much of the panic around “fertility collapse” stems from a gradual reduction of birth rates over the past century—that’s really happening. In April 2024, the CDC reported that the U.S. fertility rate dropped to a “historic low.” What was missing from the CDC’s report, however, was, of course, the sensationalism that private news media attached to this finding. Look how flat and boring this is:

The general fertility rate in the United States decreased by 3% from 2022, reaching a historic low. This marks the second consecutive year of decline, following a brief 1% increase from 2020 to 2021. From 2014 to 2020, the rate consistently decreased by 2% annually.

The CDC’s report includes interesting findings that, reading between the lines of their droll language, sounds like celebratory progress, not alarmist disaster:

2023 birth rates:

declined for women ages 20–39 years were unchanged for females aged 10–14 and 40–49.

The birth rate for teenagers aged 15–19 was down 3% in 2023 to 13.2 births per 1,000 women.

The birth rate for women ages 20–24 (55.4) reached a record low.

The cesarean delivery rate increased for the fourth year in a row to 32.4% in 2023; the low-risk cesarean delivery rate increased to 26.6%.

The preterm birth rate was essentially unchanged at 10.41%.

I’ve added emphasis because it matters who we’re talking about when talking about the birth rate declining. The decline is concentrated in two age groups: teenagers aged 15-19 and very young adults aged 20-24, and it’s safe to say that the decline in the 20-39 age group is being driven by the historic low in the 20-24 group. I think most people would celebrate a reduction in teen pregnancy and pregnancy among very young people who can’t afford a family.

This is excellent news. Teenage girls (and boys) aren’t ready to be parents. If Pete had a hard time making the decision not to be a parent, fifteen-year-olds certainly aren’t ready for that decision.

More Omitted Context

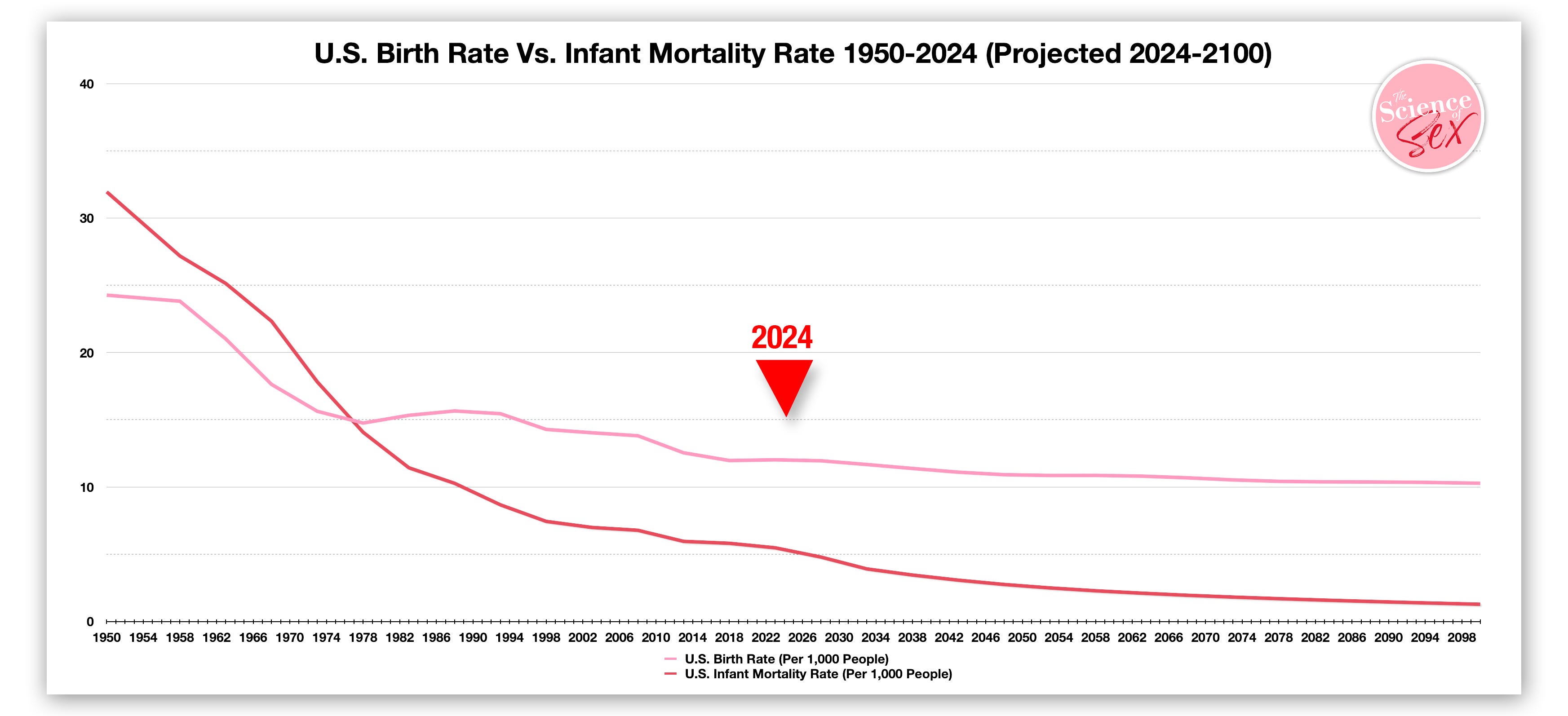

Both the deranged and the soft versions of the theory omit vital context. Here’s a chart from the United Nations World Population Prospects 2024 showing the gradual birth rate decline from 1950 until 2024. Everything to the right of the 2024 mark is the UN’s projections for the future:

As you can see, the birth rate decline began in the late-1950s and has continued. This much isn’t up for debate. But the question that isn’t answered when we look at birth rates alone is why this is happening, and that lack of context creates a vacuum for people with political or economic agendas to fill. The political right-wing fills that vacuum with discourse about how women’s liberation has been a “disaster,” and we might need to excuse some radically totalitarian measures to solve the problem.

News outlets employing the soft version prod readers to fill in the blank with their own beliefs, which is often what they’ve seen elsewhere, which is often noise from the right-wing who’ve been beating the drum about this topic. Look what happens when we compare birth rates with that missing context—the infant mortality rate.2

These are two separate statistics used to understand population dynamics: birth rate measures how many people are being born, and infant mortality measures the survival rate of those infants until their first birthday. But they’re intertwined.

The birth rate is the number of live births per 1,000 people in a population during a specific year. It measures how many children are born, regardless of their survival. Infant mortality, on the other hand, refers to the number of deaths of infants (usually defined as children under one-year-old) per 1,000 live births in a given year. Knowing how many babies are born only tells you so much, and it’s important to know how many of those babies are surviving into childhood and later adulthood (and, if they aren’t, why).

When we compare these, we quickly see that there are fewer births, but significantly fewer babies are dying before their first birthday thanks to medical advancements. Omitting this context is deception, and yet, almost everyone does it. If the infant morality rate is falling faster than the birth rate—and it is—that means more babies are surviving to become toddlers, and, ostensibly into adulthood, than before.

Any discussion of “fertility collapse” that doesn’t mention this is suspect, as they’re excluding a massive part of the equation. Now, let’s take a look at what happens when we compare those two trends with the U.S. population:

The fallacious, fourth-grade reasoning becomes immediately obvious when we think about it for more than a second. The population has only grown over the past century. Far from “population collapse,” the population is and has been expanding and is projected to continue its growth until about the end of the century.

It’s one of those “how-did-I-not-realize-that-until-now” moments.

A Case Study in “Collapse”

As I pointed out in the BBC’s sensationalist article on the subject, a lot of the reporting and research excludes nations that don’t fit the narrative. While fertility rates are declining in some parts of the world (notably in Europe, Japan, and South Korea), global population growth remains positive. Many regions, particularly in Africa and South Asia, still experience high birth rates. According to the UN, the global population is projected to reach nearly 10 billion by 2050 before plateauing. In other words, fears of a widespread "population collapse" are exaggerated when, globally, many populations are still growing—and some have already “collapsed.”

Wait, what? Yes, there is one place where the worst of the “fertility collapse” theory as already manifested—and that place is Japan. Here’s a chart of Japan’s birth rate:

Japan’s birth rate has been about half of the U.S. birth rate for almost ten years. Many of these fears are reproductive anxieties masquerading, consciously or unconsciously, as economic concerns. It’s understandable that this would alarm people who are concerned about the future. After all, we’re told that we aren’t creating enough babies to replace the people dying, which means the population will contract, which means the economy—which is based on growth—will also contract, or so the theory goes. We have words for this, and not very nice ones—we call it an economic recession or depression.

But Japan disproves this hypothesis as a case study. Japan went from having the “Lost Decade” of recession in the 1990s to being the third (now forth) largest economy in the world. In fact, Japan’s total population has already begun to shrink:

If population decline by itself was enough to send the economy into a tailspin, Japan would be falling apart right now. But it’s not. It’s robust and currently growing. Now compare Japan’s population with the U.S. population (and future projections):

Japan has managed to maintain a robust economy even as their population shrinks through a combination of innovation and technological developments. They found more efficient ways to do things. This is what really irks me about this discourse, and it’s why I say it’s reproductive anxiety (and misogyny) masked as economic concerns: because the solution is never to do things more efficiently, but to force women, by law or by piling on more unrelenting social pressure—to plop out more babies.

The doomsayers who are pounding the drum and screaming that we need to force or coerce women into making babies ignore the fact that there are many ways to structure an economy that isn’t reliant on making women into baby factories.

The Economics of Families

The irony in the lack of meaning when it comes to having children is that panic is one big reason people are less likely to settle down and have kids. So, when we panic about people not having kids, our panic breeds the very same flavor of uncertainty that gives people pause about having kids. It’s a vicious cycle. If your goal is to make people excited about having children, this is empirically the worst way to do it.

As Christina Emba excellently detailed in her The Real Reason people Aren’t Having Kids, published in The Atlantic in April, countries across the globe, like the United States and France, have tried to incentivize having kids with economic carrots, like tax breaks. These measure have invariably failed because they don’t address the underlying reason people aren’t having kids—that having kids is a massive decision imbued with immense meaning that people don’t flippantly make to save on taxes. This gets to the root of our perspectival distortions about building families.

The fact that so many people—especially men—have such a hard time envisioning restructuring society to accommodate women’s preferences and desire to have or not have children is frighteningly telling. Does it not show how much we, as a society, devalue women’s choice in the matter? Are these myths about population collapse one Jenga block in the tower that’s driving the anti-abortion sentiment? I think so.

Ultimately, the panic surrounding fertility rates and population decline is driven by reproductive anxiety and, in some cases, misogyny. People are bombarded with messages about the need to have children, yet fail to address the underlying fears and uncertainties that prevent them from taking that step. It's important to recognize that there are many ways to structure an economy that don't rely on pressuring women to have more babies. By understanding the complexities of reproductive anxiety and societal pressures, we can work towards creating a more supportive environment for individuals and families to make informed choices about their futures.3

I’ve expanded on this piece with the article The Fertility Crisis Debunked: Addendum, which goes further in depth, covering the sperm decline “crisis” more thoroughly, the testosterone decline, and expands the “fertility collapse” debunk. This is the stuff that was left on the cutting room floor when I edited this one, but it’s extremely enlightening for those who want to read the nuances of why these hypotheses aren’t workable.

“Infant” is defined as a baby who hasn’t reached its first birthday.

I’ll have more to say about this in future pieces on it, but for now, I’ve decided to leave it at this for brevity’s sake and will collect my notes and research fore those future pieces.

Thank you universe for someone putting out the counterargument. I am so sick of reading these hyperbolic, hysterical claims of "population collapse"! And no one ever offers the counter, mostly because I think it just seemed obvious or maybe even gauche. But now that so many are intensifying this drum beat and people like Elon Musk (who has blatantly said he actually *hopes* to accelerate exceeding Earth's carrying capacity because it will prompt humans to invest in his goal of going interstellar) are blasting out these false proclamations of gloom and doom, it does need to be addressed.

Traffic, traffic everywhere, yet teetering on the verge of extinction. Never mind there are a billion more people than there were just ten years ago.

With eight billion and counting already on the planet, I'm not too nicked about women's unwillingness to breed (totally get it, I never did and never regretted it). Elon Musk just wants more cheap labour and he's not spending enough time with any of them. Take parenting advice from Elon Musk like you'd take marital advice from Donald Trump.